15 min read – Characters: 24337

Over the past few months, I have been furiously listening to countless records from the past decade to try and finalize my list. As it turns out, there were many spectacular albums in the 2010s and it was unbelievably hard to cut it down to only ten albums. As a result, I have included a runner up section which houses albums that narrowly missed the top ten. The rule I made for the top ten was that there could only be one album per artist to make sure that there would be a mix of different genres and artists on the list. Enjoy!

Runner Ups

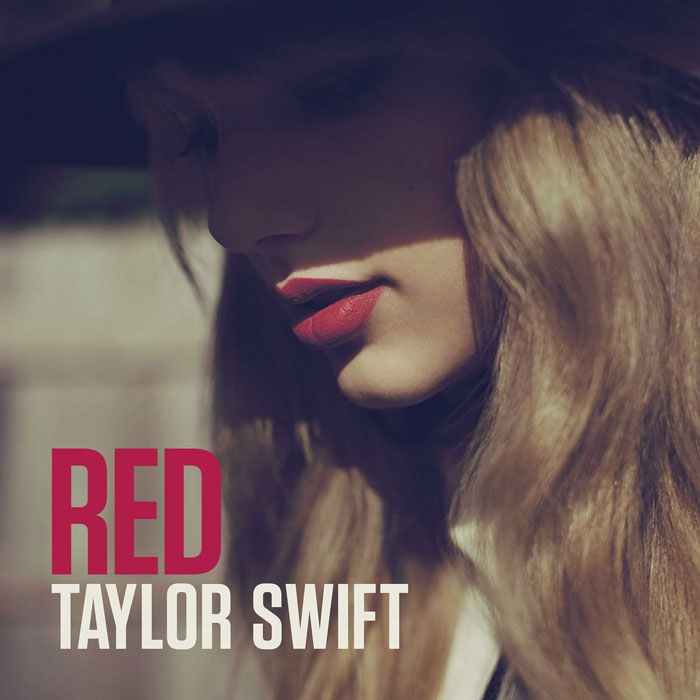

1989 – Taylor Swift

What happens when you combine pop powerhouses Max Martin and Jack Antonoff with a high-profile singer/songwriter who wants to transition into pop music? It turns out that the result is exactly what you would expect: pure magic. The story is simple: love and life in New York City. However, the journey through it all is soundtracked immaculately. Whether she’s saying goodbye to the haters on “Shake It Off” or being a “nightmare dressed like a daydream” on “Blank Space”, Taylor Swift has never been more infectious.

Every synth is perfectly placed, every vocal the perfect balance of passion and restraint, and she genuinely sounds like she is having the time of her life. As a result, 1989 could easily be a “greatest hits” record for any other pop artist. Songs like “Style”, “Out of the Woods”, and “All You Had To Do Was Stay” could make even the harshest critics tap their toes. There was a lot of initial hesitation for Swift’s pop crossover, but it is no doubt that the result was absolute pop perfection.

IGOR – Tyler, the Creator

Many will likely remember Flower Boy as their favourite Tyler, the Creator record. However, IGOR is still equally as impressive and finds Tyler’s production skills at their most advanced and cohesive to date. He has a way of never creating the same album twice and IGOR is no exception as it veers pretty far from Tyler’s typical hard-rap style into silkier R&B jams. Yes, the album is a breakup album which can, at times, be an oversaturated market. However, Tyler’s lo-fi and layered approach to this concept is one of the most interesting entrances into the category to date.

The radio-ready pop of “EARFQUAKE” and “I THINK” are immediate draws but more experimental R&B cuts like “A BOY IS A GUN”, “GONE, GONE / THANK YOU”, and “ARE WE STILL FRIENDS” pack more than enough punch to propel the album to an epic finish. IGOR also plays strictly by Tyler’s rules which may be the most interesting part of the record. He makes features from Lil Uzi Vert, Playboi Carti, Solange, slowthai, and Kanye West all sound like another dimension of his established soundscape palette. Tyler may feel like he is the puppet of his love interest but when it comes to music it is clear that he is the puppeteer.

Astoria – Marianas Trench

As a Canadian band, Marianas Trench has long been overlooked by the world at large. In 2011, they were at the height of their career and even started to gain international attention. Suddenly, the lead singer, Josh Ramsay, broke off his engagement, found out his mom had dementia, and ended up in the hospital. This terrible spiral of events caused them to eventually release Astoria four years later. The wait was well worth it.

If you couldn’t already tell from the Goonies-inspired title, the band drew on the music and culture of their childhood to tell of one of the band’s darkest periods. The 17-track magnum opus follows through the emotional pain of Josh’s last four years through the addictive pop of “Burning Up”, heartbreak of “Dearly Departed”, “Wildfire”, and “Forget Me Not”, and the Toto-inspired highlight “Who Do You Love”. The band ventures into uncharted instrumental, vocal, and conceptual territory, with every track striking gold. Complete with sweeping instrumentals, stunning synths, Queen-esque harmonies, and orchestral interludes, Astoria is truly a blockbuster that any true music fan would not want to miss.

Top Ten

10. Golden Hour – Kacey Musgraves

Kacey Musgraves’ old soul brought her success within the country music community fairly quickly. Her plucky guitar and traditional country sound was one that would never go out of style and could continue to be successful. With the release of Golden Hour, Kacey decided to instead become an innovator instead of an imitator by swapping out her old style for techniques common in pop and hip/hop communities.It is no wonder that some found it difficult to view Golden Hour as a country album as Kacey’s vocals seem relatively polished and the ragged, plucky nature of most modern country songs is entirely absent.

Everything seems to shine on the record as Kacey takes an inventive approach to country clichés such as on the songs “High Horse”, “Space Cowboy” and “Velvet Elvis”. She’s not singing about beer, tractors, short skirts, or honky tonks. Instead, Kacey tells the story of her own hardships and loneliness while assuring listeners that “It’ll all be alright”. It’s a relatable and intimate experience that seems to drift through the air like a light breeze on a summer’s day.

Golden Hour marks a mature turning point for Kacey Musgraves and unlocks a world of possibilities for her future sound. Every track is expertly written and produced to a near-perfect degree. She’s never sounded more convincing and beautiful than on songs like “Butterflies”, “Mother”, and “Rainbow”. It’s pristinely polished, bravely innovative, beautifully intimate, all the while showcasing the true possibilities of breaking genre boundaries and making something you believe in.

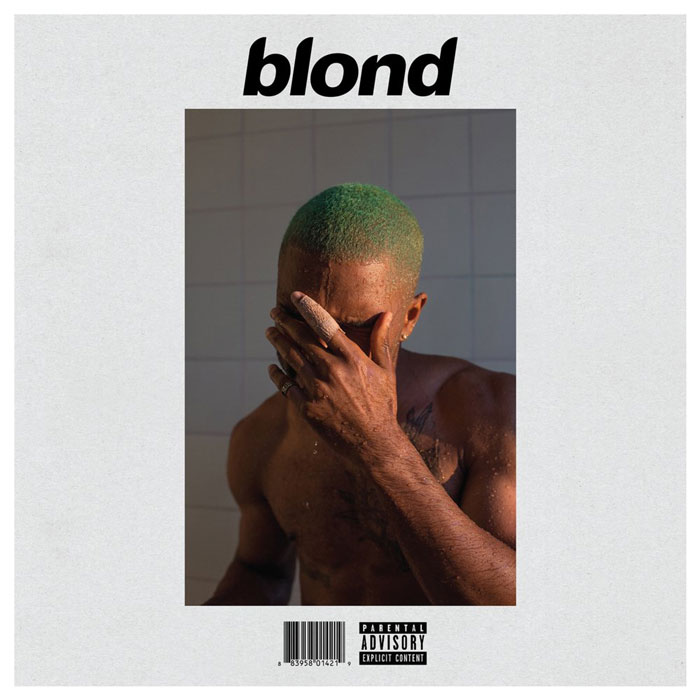

9. Blonde – Frank Ocean

Frank Ocean received, or rather, commanded everyone’s attention with the release of Channel Orange near the beginning of the decade. From then on, fans were eagerly awaiting his next record, tentatively titled Boys Don’t Cry. After many delays and much disappointment from fans, Frank Ocean returned on one fateful night in August of 2016. He dropped two albums over that weekend, one being the visual album Endless to fulfill his prior commitment to his old label. The other was the critically applauded and experimental Blonde.

On this record, Frank traded out the R&B-pop fusion of “Thinking Bout You” and “Forrest Gump” for postmodern ambience and R&B. The swaying “Nights” follows a similar two part structure to “Pyramids” but seems much more airy and fluid. The stacked instrumentals on songs such as “Pink + White”, “Pretty Sweet”, and “Futura Free” seem to almost drown out Frank Ocean, as if he has become nothing other than another layer in much larger sonic mural. However, songs like “Ivy”, “Solo”, “Self Control”, “White Ferrari”, and “Godspeed” find Frank singing over very minimal production and pack enough emotional punch to make Arnold Schwarzenegger break down.

The album also features guest writing credits and vocals from high profile artists like Paul McCartney and Beyoncé which is a testament to how well-respected Frank is within the music community. Both Channel Orange and Blonde are legendary within their own right but differ so much on almost every level imaginable making Frank Ocean one of the most fascinating artists currently working in music. However, Blonde is truly one-of-a-kind and is a record that will go down in history as a marvel of the imaginative possibilities of recording technology and artistry.

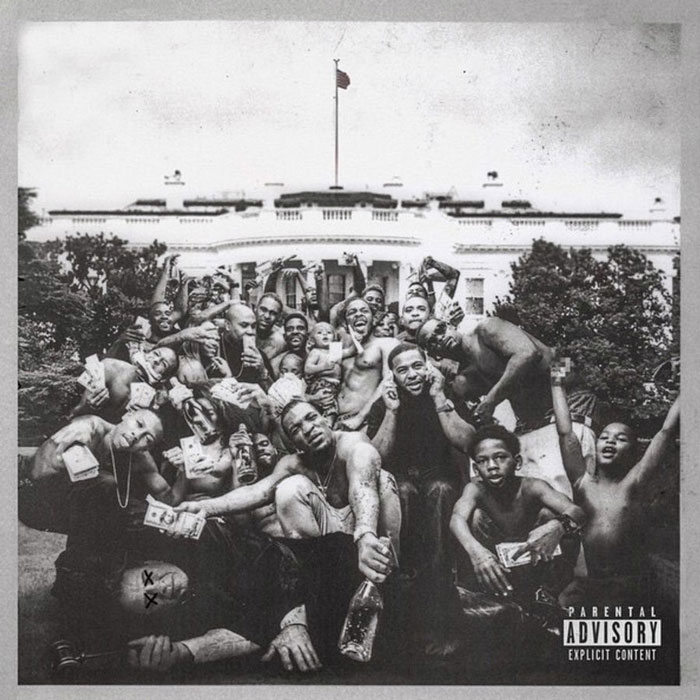

8. To Pimp a Butterfly – Kendrick Lamar

It is no doubt that Kendrick Lamar is one of the greatest artists to emerge during the decade. His poetic style and extremely sophisticated approach to hip/hop and storytelling has gained him a lot of attention, many accolades, and even scholarly courses dedicated to analyzing his works. To Pimp A Butterfly, however, is Kendrick Lamar at his creative peak and even inspired David Bowie for the direction of his final album, Blackstar.

Kendrick Lamar broadens his focus on this record to discuss the construction of the African-American identity, institutionalization, police brutality, and black pride. For an album prominently focused on race, Kendrick draws on typically African-American dominated music styles such as hip/hop, jazz, and R&B. It’s a beautiful culmination of African-American art and influence led by one of hip/hops most imaginative MCs.

Kendrick uses the practice of pimping as a metaphor for the treatment of African-Americans throughout history. He also uses the idea of a cocooned caterpillar and a butterfly to talk about self-image and institutionalization within black communities. The wit and relevancy of each of Kendrick’s verses on this record is a work of literary genius. Tracks like “These Walls”, “u”, “For Sale (Interlude)”, “How Much A Dollar Cost”, and “Complexion (A Zulu Love)”, “i”, and “Mortal Man” demonstrate this to a degree unparalleled by any of his contemporaries.

Additionally, Kendrick does not bow to genre pressures and focuses more on substance and concept than making every track a “head-banger”. The impact of the content hits a lot harder than many of the beats on the record as a result which is extremely inventive and interesting to follow. To Pimp A Butterfly finds Kendrick Lamar at the top of his game with respect to every aspect of the record and is no doubt one of the most relevant and inventive records to be released within the last 20 years.

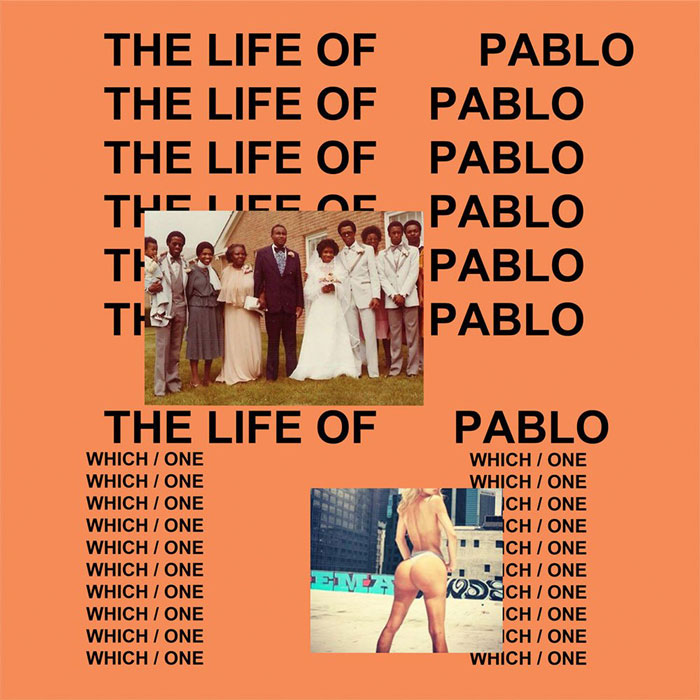

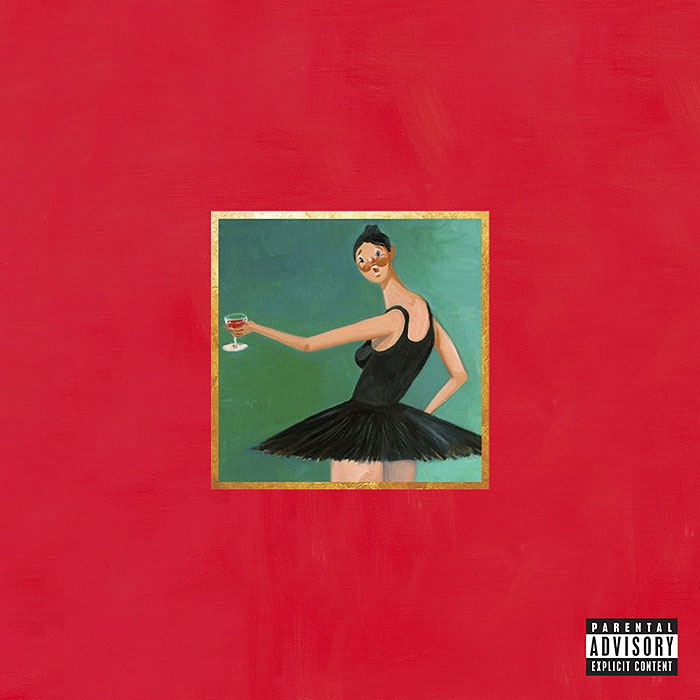

7. The Life of Pablo – Kanye West

Not many artists could make an album like The Life of Pablo work. If anyone could though, it would be Kanye West. On the surface, The Life of Pablo feels very much like the rough, unfinished cover art and perhaps that’s the beauty of it. The stunning “Ultralight Beam” and instant earworms like “Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 1”, “Famous”, “Waves”, and “Fade” are immediate crowd pleasers. But some of the deeper cuts like “FML”, “Real Friends”, and “Saint Pablo” really propel the album through the narrative Kanye has constructed, or rather, lived.

This album is one of contradictions and juxtaposition. As an illustration, there are features from both Chris Brown and Rihanna which, considering Chris’ past abuse of Rihanna, would be in quite poor taste on any other album. Yet, on The Life of Pablo it seems right at home. The controversial Taylor Swift lyric and the lyric about bleached – well – y’know all follow the gospel-infused opening track “Ultralight Beam” which features a prayer for those who feel they’ve “gone too far” from none other than Kirk Franklin. This constant imbalance between the spiritual and secular has not only been extremely popular in gospel music throughout its history but also within Kanye’s own life.

Kanye’s honesty and braggadocious persona create a dazzling and autobiographical experience. By the time the second half of the record comes around it’s no surprise that Kanye is struggling with his identity, faith, and family, as expressed by tracks like “Real Friends” and “Wolves”. It is clear that although Kanye wants to focus on the highlights and perks of the fame and women in his life, he cannot move past the feeling that he is stuck in a fantasy much darker than he ever imagined. Musically, Pablo features a multitude of samples, artists, and production styles. For example, “No More Parties in LA” has more of a vintage rap feel which contrasts with the gospel feel of the first two tracks and the experimental nature of “FML”.

Overall, The Life of Pablo is very hard to discuss in such few words as this. It is an album that is quite literally always evolving as Kanye continued uploading new versions of the songs after the album’s initial release. It is a sprawling journey through multiple genres and stories, until Kanye’s facade cracks on the stunning finale “Saint Pablo” which finds Kanye wrestling once again with his faith and family. The Pablo referred to in the title is the Biblical figure Paul, who was converted to Christianity after initially oppressing Christians. Once described as “a gospel album with a lot of swearing” The Life of Pablo may not be the gospel revival that would come later in Kanye’s career, but it is an essential first step.

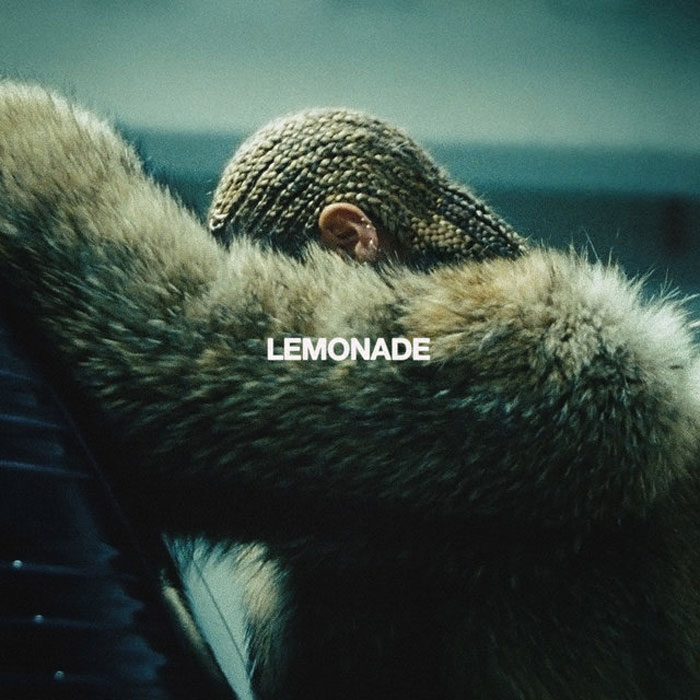

6. Lemonade – Beyoncé

The sparse, vocal-heavy opening track “Pray You Catch Me” makes it clear: this is no ordinary Beyoncé record, or record in general. This is a journey. Over the albums twelve tracks, Beyoncé discusses jealousy, infidelity, anger, heartbreak, and finally healing, restoration, and forgiveness. Oh, and if that wasn’t enough there’s the truck-rattling Black Lives Matter anthem ‘Formation’ to top it all off at the end. However, this is not Sasha Fierce or the flawless persona from her self-titled album. This is the journey of one of the most buzzworthy artists of the decade at one of her darkest moments. Beyoncé has never been more vulnerable and yet it seems that in her weakness, she has also never been stronger.

The music itself expresses her internal strife as it hops between numerous genres such as reggae, rock, country, pop, hip/hop, and more. Beyoncé not only experiments in this uncharted territory but effortless nails every one and, dare I say, even improves on some. The heartbreaking ‘Sandcastles’, explosive ‘Don’t Hurt Yourself’, and the thumping ‘Daddy Lessons’ are among the albums many highlights. Everything Beyoncé does on this record comes with a twist, one only Queen Bey herself could add to the “lemons” she’d been handed.

Perhaps what is most impressive about this album though was its ability to dominate the conversation in 2016, a year already full of critically acclaimed releases from the likes of Frank Ocean, her sister Solange, and Kanye West. It was Lemonade’s year and everyone knew it. That’s what made Adele’s acknowledgement of this even more bittersweet when she had beat Beyoncé at the subsequent Grammy awards for Album of the Year. Nevertheless,Lemonade will continue to dominate the conversation and forever be remembered as a groundbreaking moment in musical history.

5. A Seat at the Table – Solange

Beyoncé always seemed to outshine her sister. She was in a massively popular girl group and became one of the biggest popstars on the planet. Solange, on the other hand, was involved in an infamous elevator incident with her sister’s husband which was more publicized than her entire career up to that point. However, the release of A Seat at the Table would change everything.

Not only is A Seat at the Table an important record conceptually but it often relies on minimalistic production and simple melodies to sustain all 21 tracks. This pays off in a way that only Solange could orchestrate. Whether she’s talking about self-care, lost loves, or her struggles as an African-American woman in modern day America, she does so with exceptional grace. Sonically, the record is very cohesive. Every track seamlessly transitions into the next making it more of an experience than a compilation of songs. It is clear that Solange’s knowledge as an artist goes far beyond songwriting as every aspect of the record is utterly flawless.

The interludes throughout the album also provide more interesting windows into the African-American experience during segregation and the present day. Not only are they entertaining and informative, they feel essential to the album’s success by tying every aspect of Solange’s story to her identity and heritage. At one point, one of the featured guests denounces “reverse racism” by providing such a simplistic explanation of why black pride is integral to society that a child could understand. This conversation should not have to be had in our society and yet it has never been more important. It is a true testament as to why we need more diverse voices in Hollywood and the music industry. Solange successfully commands an exceptionally moving album lyrically and instrumentally and spreads love and empowerment to black communities throughout the world in a way that has never felt more authentic and relevant.

4. Beyond Control – Kings Kaleidoscope

“But still this faith I hold/is my reality” is the bold proclamation that comes within the final minutes of this album. And when it does come, it feels as if it’s been ripped right from midst of an intensely personal and difficult journey. Although the Christian hope in Jesus is at the center of this album, it’s not all sunny skies and rainbows. Tracks such as “Most of It”, “Gone”, and the cleverly titled “Lost?” all follow along on Kings’ faith journey of learning to be okay with what they cannot control and gaining dominance over their fears. However, this all occurs before their breakdown at the end of the album revealing that this is no hero’s journey but instead one of continual wrestling, praising, pain, and growth.

Instrumentally, the album follows a rather optimistically jazzy flow, with hints of subtle samples and layers throughout for the first half. The interlude titled “Friendship” is just the band messing around with melodies in the studio capturing the kindred spirit that lies behind most of the tracks. In the second half of the album, the band falls into more stripped back sonic textures as they wrestle more with their fears and insecurities. Even the closing song “Trackless Sea” is rather mellow until a rather chaotic praise snippet bursts forth after a brief moment of silence revealing their cycle of emotions and return to praise.

Still, it is an album that deals with pain as much as it does praise such as on the controversial track A Prayer which features the line “where the fear is f—-ing violent” taken from the lead singer’s journal while suffering with severe anxiety. The industrial instrumentals sound as if they’re scraping along the ground, weary from a long battle. In the same breath it asks “Jesus where are you?/Am I still beside you?” while affirming and finding comfort in His death and resurrection. Kings Kaleidoscope prove time and time again that they are not afraid of the tough questions but at the same time are okay with not knowing all the answers. It is a uniquely human album that delights in the trials and triumphs of faith and the human condition, all the while accepting that it is truly beyond our control.

3. Coloring Book – Chance the Rapper

It has been said that good things always happen in threes. For Chance the Rapper, this meant three beloved mixtapes, the Holy Spirit, and his iconic three hats to commemorate all of this. Coloring Book marks the third entry in his mixtape trilogy and swept Chance into the mainstream. The success of this mixtape even caused the Grammys to change their qualification policy to allow albums exclusively available on streaming platforms to be able to be nominated for awards. Perhaps it was poetic that this allowed Chance to also win three Grammys for Coloring Book.

But Chance would attribute this much luck and success also to God as Coloring Book finds him boldly expressing his faith across a plethora of expertly produced and addictive gospel beats. Coloring Book practically perfected the gospel-rap fusion that had been started by artists like Kirk Franklin and Kanye West. Every single song feels as if it’s been lived in and grown for a significant period of time. Take the mellow “Summer Friends” a tribute to those relationships that only exist for a short period in one’s life. The Francis and the Lights feature is perfect, Chance’s verses are witty and feel like a confessional instead of a rap. Even Jeremih’s feature blends perfectly into the sonic landscape of the song. Each track follows this pattern of expertly selected guest vocals, fitting verses from Chance, and joyous instrumentals.

He talks about his family, his faith, and his friends with a level of optimism that is unheard of. With the world seeming so dark at times, this record shines like a light. It would be impossible to not burst out in a grin while hearing tracks like “All We Got”, “No Problem”, “Angels”, and “Finish Line/Drown”. The fact that this record is only a “mixtape” is also stunning. No wonder Chance sings “it seems like blessings keep falling in my lap” because Coloring Book feels heaven-sent.

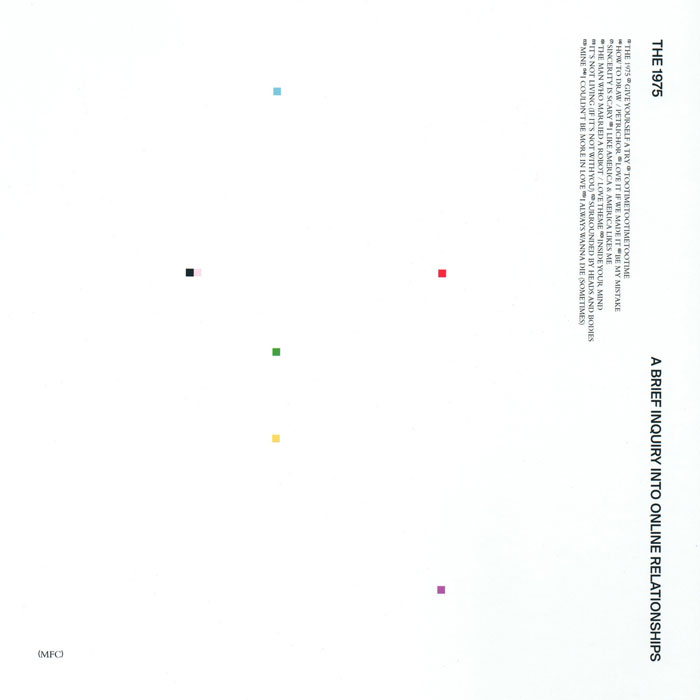

2. A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships – The 1975

To think that at the beginning of the decade The 1975 had not even released their debut album is mind boggling. Their progress from small indie band to politically-charged, arena rock icons has been a fascinating journey to follow. While their first two albums seemed to overstay their welcome, A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships feels shockingly relevant and mature.

The instrumental, sonic, and lyrical styles have not changed but have been injected with more substance and wisdom than on their previous efforts. Every track is addictive and seems carefully chosen. Even the partially ambient detours à la “The Man Who Married a Robot/Love Theme” and “How To Draw/Petrichor” both fill necessary holes in the album’s narrative while being some of the most beautiful moments on the whole record. The paranoid and spastic nature of “Give Yourself a Try”, “I Like America and America Likes Me”, and “Love It If We Made It” is infectious and highlight the fears that many hold with our access to such a vast amount of information, good and bad. But the thought put into this record goes far beyond the vocal performance and instrumental landscapes. “It’s Not Living (If It’s Not With You)”, “Be My Mistake”, and “I Always Wanna Die (Sometimes)” all shed a strikingly honest and personal light on drug addiction, infidelity, and suicide respectively. Each song seems to showcase another new example of how technology is mediating our relationships with both things and people.

It is a message that has previously been explored by various artists throughout music history, most famously Radiohead. However, The 1975 take it to the next level by using modern recording technology like auto tune to showcase the mechanization of our humanity and even use a gospel number to discuss our fears of being sincere with one another. The message is not only one that is continually important but also one that is necessary for anyone alive right now.

1. Melodrama – Lorde

Clocking in at 11 tracks and just over 40 minutes, Melodrama is a testament to every great thing about pop music. In the time between this album and Pure Heroine, Lorde had grown up, won a Grammy, and lost a significant relationship. The highs and lows of her experience are showcased here and form the basis of the record. So yes, Melodrama is a breakup album. It is a coming-of-age album. It is a pop album. But it is also so much more than that.

The opener “Green Light” is a peculiar track as it violently switches from minimalistic opening chords to a proper pop song courtesy of Jack Antonoff. The tone grows darker with the whisper-pop and heavy synth vibes from “Sober” and “Homemade Dynamite”. Suddenly it clicks: the album is set at a house party. What better place for a teenager to contemplate their life?

Every song that follows is a new dimension of heartbreak that draws you close and rips you open. The production is beautiful and cohesive, each track oozing into one another while still feeling intimate. It is clear that Lorde has never been in more command of her craft. By the time “Perfect Places” rolls around, Lorde has felt deep pain and regret, acknowledged her romanticism of the past, and realized her true self-worth. She is now free to return to the party while remembering that nothing is ever truly perfect in this life.

This album does not succeed by having a large persona or grandiose production. Rather, it retreats into the corners of your brain and feels like a heartfelt letter from a close friend. Lorde puts her entire soul into every breathy note and synth and focuses more on the quality than the quantity. Emotions are amplified and every track sticks the landing. Her journey back to being whole is one that is melodramatic but captures the deeply human truths about self-image, growing up, getting your heart broken, and putting the pieces back together again.

Thanks for reading!